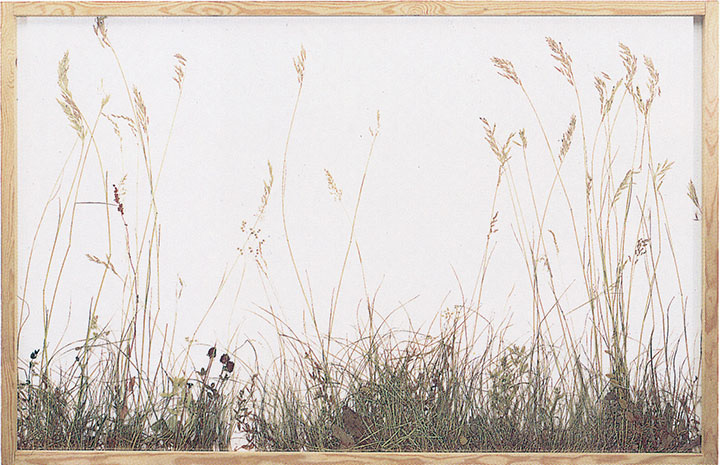

'rasenstücke'

[66] Among the earliest and most truly accurate (and most beautiful) representations of the botanical actuality of shrubs and flowers are in mid-fifteenth century drawings by Pisanello, Jacopo Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci, and in details of Flemish painting by artists such as Jan and Hubert van Eyck and Hugo van der Goes. It is in that period that the truly naturalistic rendering of plant life, based on careful observation and study of the real thing, began in modern European art and science. Such drawings were often made from the life as studies for details in paintings, mostly devotional. This was certainly the case with Albrecht Dürer, whose marvellous watercolour study of Irises (1503), held by the Kunsthalle Bremen, was carefully utilised in the painting of the London National Gallery Madonna with the Iris, executed by his workshop in 1508. It is to Dürer, certainly, that we look, also, for the first accurately observed study of plants in a natural ecological community (it might best be described as a habitat fragment): this was the famous Das Große Rasenstück (The Great Piece of Turf), completed in 1503.

Speaking of his own version in relation to Dürer's masterpiece, de vries exclaimed; "but mine is more real!". He was, of course, speaking truly, but his own version is no more a simple botanical or herbarium specimen than is Dürer's, and is susceptible of as many 'readings' as that early masterpiece of complex naturalism to which it explicitly pays homage. Both works are informed by love and reverence for the natural world, both are manifestations of wonder

[67] at the beauty, diversity and complexity of the commonest plants of the field. Both are in their different ways symbolic, even as they appear to present nothing more than a piece of reality, a humble natural fact. Although both seem to project an objective reality that places them in certain respects within the domain of scientific investigation, they are both without doubt works of art.

But there is an interesting paradox here, a paradox which takes us directly to the problematic heart of de vries's project, and which raises the most crucial critical questions about what we mean when we speak of 'the real'. Dürer's wonderful painting depicts its common field plants with the exactitude of observation that makes it possible not only to identify the species and name the plants but, also, if we so wanted, to use it as a guide to identify other specimens of the same species.

[...]

[68] Each of de vries's own rasenstücke is likewise a group of meadow plants found (literally so) growing together, and framed and named in such a way as to deliberately remind us of its famous predecessor. de vries's rasenstücke present us with unique examples and to identify them - to name them - we would require precisely the kind of skilled identificatory depiction that we first find, in the modern era, in the drawings of Pisanello, Leonardo and, of course, Dürer himself. For such representations have behind them the force of an idea, the idea of the species, which is logically related to the idea of the genus, and which is a mental construct, an abstraction, a 'fact', not a thing. (That Linnaean taxonomy was not invented until later does not affect this.) Herein lies the paradox: no ideas but in things! But things acquire the identity that makes them concrete to the mind, makes them knowable, only through the abstractions of words and classifications. It is, necessarily, a paradox that de vries, the scientist-artist is certainly aware of and must live with. It provides him with a playful freedom.

[source: Mel Gooding, herman de vries. chance and change (Thames and Hudson : London 2006) 66-68.